Encountering God in History

Author: John Schofield

John Schofield is a former Chair of St Mark’s CRC, and past Principal of an Anglican Ministry Training Scheme. |

Three things just in the title need exploration

-

God

-

History

-

How to encounter anything in history

Let’s take the first; we are talking about the God believed in by Christians, the God of the so-called Judaeo-Christian heritage; but for us specifically the God who revealed Godself in human form in the Incarnation.

But

What is history?

And how do we encounter anything in history

These are some of the approaches to history that we meet up with in various guises.

-

History is bunk (attributed to Henry Ford)

-

History is something that didn’t happen, written by someone who wasn’t there

-

History is a bunch of tricks played on the dead (Voltaire)

-

‘The version of the past that people have decided to agree upon’ (Napoleon)

-

‘His-story’; ‘In history, God is revealed’ (Pannenberg, 1961)

-

History is lists and chronologies. But ‘So far from history being an innocent attempt to list events in a sort of neutral space, history tries to identify more clearly what its own subject is’. (Illustrated by the question ‘What happened in 1066?’ and the variety of answers you’d get) (Williams, 2005:4)

-

‘We can only fully understand the present in the light of the past’ (E H Carr)

-

Schleiermacher: We are historical beings, living in history, shaped and changed by it. Therefore the understanding of the Christian tradition in ever changing circumstances is the heart of theological activity. The function of leadership in the Church can only be adequately performed on the basis of a highly developed consciousness of history.

If all this is history, how do we begin to encounter God within it?

Which brings us neatly to encounter: do we only allow ourselves to encounter what we want to encounter, or do we let the encounter with the strange, the different, the hidden, the mysterious, challenge our presuppositions and pre-understandings? Are we satisfied with projection of our needs and quests onto God, or do we let God interrogate us?

How the Jews encountered God in history.

The Jewish Scriptures show us how the Jewish people encountered God in history and also how the people who later edited the history thought they encountered God there. It’s worth noting that of all the ancient people the Jews had an idea of history that most approximates to ours.

Most of the Old Testament is a story of an historical process initiated by Yahweh. Different strands have different starting points (Creation in general; creation of Adam and Eve in particular; the call of Abraham), but all have same sense that Yahweh intervenes decisively at various points. And some of the Psalms (eg 77, 78, 105, 106) give voice to this. The Catholic missiologist Andrew Walls reminds us how this impacts on us

The Christian is given an adoptive past. He (sic) is linked to the people of God in all generations (like him, members of the faith family), and most strangely of all, to the whole history of Israel, the curious continuity of the race of the faithful from Abraham. By this means, the history of Israel is part of Church history, and all Christians of whatever nationality, are landed by adoption with several millennia of someone else’s history, with a whole set of ideas, concepts, and assumptions which do not necessarily square with the rest of their cultural inheritance.’ (Walls 1996:9)

Somehow we have to make sense of this, and of the God we encounter as we turn the pages of the Hebrew scriptures. It is not something we can just ignore; neither is it necessarily something we can take simply at face value.

Partly this is because there is the Deuteronomic take woven into this, offering an account of the judgment on Yahweh on the infidelity of Israel (cf King John was not a good king; he slobbered and had favourites). And this introduces us to the idea of interpretation (as Polanyi reminds us, every act of knowing includes an appraisal – interpreting anything is a risky and judgemental business). And we must remember that

‘Because God works in a long and varied historical process, the perspective within the Hebrew Scriptures is necessarily one that is constantly developing and moving.’ (Williams 2005:7)

There is also Walter Brueggemann’s idea of testimony and counter-testimony, that the OT contains in itself two strands – the approved, official, normative strand that he calls the Testimony, appreciated and reached through looking at the great active verbs such as create, promise, give, free, deliver and command that dominate the Hebrew Scriptures; but within the same corpus, voices which ask

-

Where now is your God?

-

How long?

-

Why have you forsaken?

-

Is Yahweh among us?

To which the answers come

-

Here and everywhere, but in ways one cannot administer.

-

Until I am ready.

-

My reasons are my own and will not be given to you.

-

Yes, in decisive ways, but not in ways that will suit you.

(Brueggemann 1996:357)

In such uncomfortable and paradoxical way, the witness to the encounter with God demands our attention.

Reading the world

Some Christians narrow God’s activity down to the salvation of the individual soul. That is all that matters. They tend to use verses such as (supremely) John 3:16 ‘For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life’, or 2 Cor 5:19 ‘in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself’ as ‘controlling’ verses, but ignore that both are about God’s love of the world.

We have to look at something wider.

Paul provides this in more than one way

-

the agonised theologizing in Ro 9-11 about Israel

-

the creation motif

-

‘the earth and its fullness are the Lord’s’ (quoting Psalm 24)

-

‘the whole creation has been groaning in labour pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies.’ (Romans 8:22-23)

-

‘[Christ] is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things and in him all things hold together.’

(Colossians 1:15-17)

In this light, ‘in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself’ and ‘God so loved the world’ offer that wider perspective, reposition the encounter.

A view among theologians, partly influenced by Augustine and

The City of God is that the historical process only makes sense in the encounter with God’s ultimate purpose to bring it all to a halt in a final judgement. We’ll return to this later.

Patterns of meaning and/vs cataclysmic event(s)

Do we look for an encounter with God in cataclysmic events or do we see God in the meaning of patterns or the patterns of meaning?

There are a number of cataclysmic events in the OT from the Fall to the Descent into Egypt, the Exodus, dire warnings of the Day of the Lord, the Exile, (and if we glance at the Apocrypha, the Maccabean wars as well). And it is easy to read the encounter with God gloomily in terms of these.

But the most significant cataclysmic event is the cross.

Hung on a cross to die

Jeered at by passers-by

Hoping he’ll catch my eye

We will be there.

But will we?

There are other ways of encountering God – there are people (perhaps of a more reflective nature) who encounter God in patterns of meaning rather than cataclysmic events and their repercussions. It is possible to see the beginning of this is the work of the prophet whose words are recorded in Isaiah 40-55, and of course in the Deuteronomic editing of history. Parts of the Wisdom literature also attest to this way of seeing God.

But back to the Cross. And the idea of ‘the X of history’ – one way of encountering God’s work in history is to observe the narrowing down of Israel’s history from the whole nation (called to be light to the nations but hiding behind rebuilt walls of purity instead) to a single man, the point of God’s utter self-identification with God’s creation. And from there it spreads out again to encompass the whole world, the whole of creation, as we carry to good news to every nation.

‘Jesus brings the earlier history to a climax, yet in such a way that the history is seen quite differently … if Jesus is the culmination of that process, his life and death will provoke an unprecedentedly far-reaching shift of perspective, and thus a major essay in historical revision.’ (Williams 2005:7)

It is an alternative to some of the eschatological readings of history which we’re going to look at next, but not inimical to all of them.

History and Eschatology

So: is the Christian project to be completed in, beyond or after history? Where will humanity’s final encounter with God happen?

God has a strange grammar of past, present and future all wrapped up together, and partly because of this you could say that Christianity is bedevilled by two entirely different approaches to the final inbreaking of God

-

Pre-millennialism – of an Adventist, apocalyptic, nature: the Kingdom will come at the end of the ages, as/after the second coming; though this carries the danger of laissez-fairing, of status-quoing: it’ll be alright in heaven. More recently this has been radicalised and politicised in the development of the endtimer/rapture movement.

-

Post-millennialism – where the emphasis is on building the kingdom now, though this can ignore the judgement of God.

This is still mirrored in the relics of antagonism between “evangelism” and the “social gospel” which were very considerable conflicts for much of the last century, and weren’t just about theology – they were also about how and where you encounter God, immanent or transcendent.

History, memory, worship and identity

Here we turn to consider the concept of ‘catholic’ as ‘Christian universality across time and space’

‘If I have read St Paul in 1 Corinthians carefully I should at least be thinking of my identity as a believer in terms of a whole immeasurable exchange of gifts, known and unknown, by which particular Christian lives are built up, an exchange no less vital and important for being frequently an exchange between living and dead. There are no hermetic seals between who I am as a Christian and the life of a believer in, say, twelfth century Iraq – any more than between myself and a believer in twenty first century Congo, Arkansas or Vanuatu.’ (Williams 2005:27)

The role of worship is of considerable significance in this wider way of viewing:

-

Christianity is an historical religion, that is a religion based on acts in history and lived out throughout the historical process of life, development and interpretation.

-

But history includes the present – it’s not just the past.

-

We are part of that present that is history, that present that is God, and it’s important that we include our own and other contemporary experiences of encountering God in our thinking about how we encounter God in history.

-

And history can give us a handle, tools for interpreting whether our current encounter is ‘valid’, is within the tradition, part of the playing field.

-

One of the ways in which this happens is through text and worship. By text I’m not so much thinking of the Scriptural text – though most worship texts are drawn from scripture – but the whole corpus of liturgical texts which we use when we meet together as the Body of Christ and especially in worship. These texts are both old and new – from Psalms to Worship Songs – and in them we, alongside countless millions across time and space, can/do/might encounter God

-

Rowan Williams’ comment about this that

What it is possible to say now with commitment and integrity is most unlikely to be exactly what was said in another era … [but] Our awareness of words that are still held in common, acts still performed, helps us read what they said within one context that we all share, the act of the Church as it opens itself to the action of the Christ who is present in his Body.’ (Williams 2005:96)

is helpful.

Amanesis

-

Central to all Christian worship is the Eucharist, where we make the memorial of Christ, we make present, active and effective in the here and now, all that God in Christ did and achieved and made possible for us.

-

As the Jews encounter the saving acts of God at the Passover meal, so we encounter God in the breaking of bread and the sharing of wine.

-

History is not confined to the past. History is the present and the future. Christ has died. Christ is risen. Christ will come again.

How not to look for God in history

-

We must beware of the danger of grand interpretations

‘we have to stand back and see the landscape as a whole – and for the sum of our ideas and beliefs about the march of ages we need the poet and the prophet, the philosopher and the theologian. Indeed we decide our total attitude to the whole of human history when we make our decision about our religion – and it is the combination of the history with a religion, or with something equivalent to a religion, which generates power and fills the story with significance.’ (Butterfield 1949:23)

-

But it is easy to fall prey to the illusion of progress, and despite this tour de force from P T Forsyth in 1917, we too easily slip into it again (until twin towers and inappropriate invasions perhaps shake us out of it)

“You have grown up in an age that has not yet got over the delight of having discovered in evolution the key to creation. You saw the long expanding series broadening to the perfect day. You saw it foreshortened in the long perspective, peak rising on peak, each successively catching the rising sun. The dark valley, the desert horrible, you did not see....The roaring rivers and thunders.... the awful conflict latent in nature’s ascent and man’s - you could pass these over in the sweep of your glance....But now you have been flung into one of the awful valleys....You are in bloody, monstrous, and deadly dark....The air is as red as the rains of hell. The rocks you stood on fall on you.”

-

Then there is the danger of too easy a reading of God in history. Christian writers of bring an assumption of God’s controlling presence in history – I’m certainly not arguing that it’s impossible to encounter God in history, but I do want to suggest that it’s a complex activity and that personal ‘wow moments’ and easy ‘God’s on our side’ readings need to be tested against a much bigger picture.

The strange and consistent God

-

God’s self-consistency is an alternative to the simplistic God’s in charge of history. Though there are difficulties with pursuing such an approach, as even this can be seen to depend on a theory of interventionism which itself problematic.

-

‘History could, for the Christian, show the faithful coherence of God’s action and nature. Telling the story of God’s acts could display in dramatic form the consistency of God’s goodness. But because the human record is anything but consistent, the historical enterprise is always going to have an element of inviting wonder at the capacity of God to maintain the steadiness of his work in the middle of earthly conflict and disruption.’ (Williams 2005:9)

-

What we encounter, even with the God we encounter, is strangeness and difference, but we should take strangeness seriously as the starting point of labour: ‘God has revealed himself in such a way as not to spare us labour; God speaks in a manner that insists we continue to grow in order to hear’ (Westcott). Rather than as a point of separation and non-comprehension we should see strangeness as demanding encounter

-

‘Language conveys meaning not because the author “puts” meaning into their words, but because words carry meaning as a result of the larger linguistic system of which they are part.’ (Lynch, 2005:137). What the attempt to understand how we can encounter God in history tries to undertake is a specific arrangement of words, images and sounds that make sense to those who read or hear it because they live and work within particular cultural conventions.

In a post modern age, which eschews meta-narratives, Christianity tells a cosmic story, and this presents us with a problem.

But the problem is not whether we encounter God in history, it’s knowing when and how we have encountered God. God has always been engaged in the historical processes, and totally and inextricably since the Incarnation. The problem is knowing what to make of the encounter, with this strange, disturbing, down-to-earth God who yet apparently remains hidden and inaccessible. I hope I have given you some avenues for exploration.

the fact [is] that the Christian faith is a historical faith. God communicates his revelation to people through human beings and through events, not by means of abstract propositions. This is another way of saying that the biblical faith, both Old and New Testament, is ‘incarnational’, the reality of God entering into human affairs.

Bosch, 181

Bibliography

Bosch, D. (1991) Transforming Mission –

Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission New York: Orbis Books

Brueggemann, W. (1997)

Theology of the Old Testament Minneapolis: Fortress Press

Butterfield, H (1949)

Christianity and History London: G Bell and Sons

Lynch, G. (2005) Understanding Theology and Popular Culture. Oxford: Blackwell

Walls, A. (1996)

The Missionary Movement in Christian History; Studies in the Transmission of Faith. New York: Orbis Books

Williams, R (2005)

Why Study the Past? London: DLT

Author/copyright permissions

Reproduced with permission.

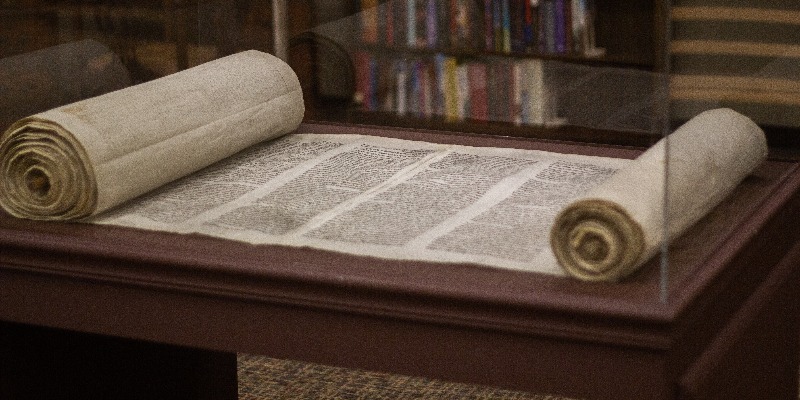

Photo Credit: Taylor Wilcox |