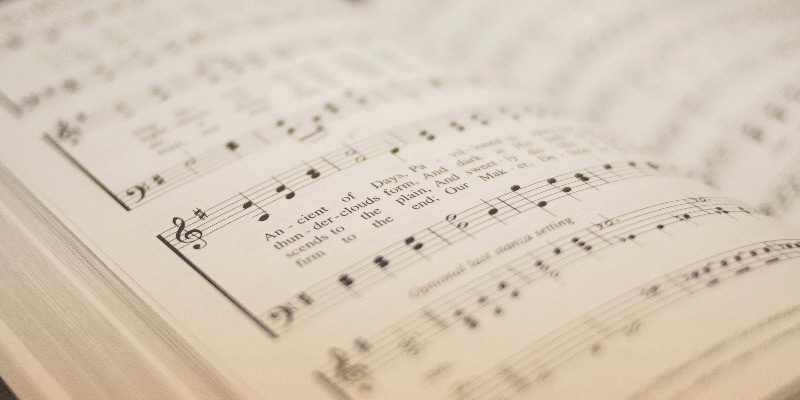

Songs of Praise?

Author: Adrian Alker

Adrian Alker was vicar of Saint Marks for 20 years until 2008 when he became Director of Mission Resourcing in the Ripon and Leeds diocese. He is currently chair of PCN Britain. In this article he reflects on the use of hymns in progressive Christian liturgy. |

It is said that the devil has all the best tunes and that might be so if we enjoy a tune but sing accompanying words which affront our intelligence, reduce ‘God’ to a tyrannical father figure watching us from his throne ‘up above’. This article is about hymns - and there are hundreds of thousands of them - and asks whether they are all an acceptable offering in our worship.

So first let’s remind ourselves of the rich history in the Judeo-Christian heritage of hymns and hymn-singing. In his letter to the Colossians, (Colossians 3.16) St Paul urges his listeners thus: ‘Let the word of Christ richly dwell within you as you teach and admonish one another with all wisdom, and as you sing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs with gratitude in your hearts to God.’ Paul would be familiar in his Hebrew scriptures of the many songs and psalms used by the people of Israel. Psalm 95 invited the people to ‘come before his presence with thanksgiving, and make a joyful noise unto him with psalms.’ Making music was a familiar element in liturgies and served then, as now, to build up the worshipping community.

Andy Thomas, former music director at St Marks Broomhill quotes St Paul, this time in his letter to the Romans “Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship.” (Romans 12:1; NIV). Andy writes:

By ‘bodies’ is meant ourselves as a totality - all our thoughts, actions, habits, relationships, etc. - not just skin and bones. Ensuring that these are ‘holy and pleasing to God’ is, according to Paul, acceptable worship. Worship is much more than the fraction of our lives that is confined to ritual or other church- based activities.

For Andy- and I agree with him- singing hymns must be in harmony(sic) with all that we think, with our integrity, our hopes and our actions. There is an old prayer said with the choir before worship, which asks that what we sing with our lips, we may believe in our hearts and show forth in our lives. But is this always so?

The crux of the matter seems to me that so often congregations in any or all denominations and settings enjoy singing hymns to a good tune,

whatever the content of the words of the hymn or sing! This is not a new issue but a debate which has had legs for decades, if not centuries.

Until the Reformation there was little controversy over the chants and hymns sung in praise of God, Jesus, Mary, the Holy Trinity, the Saints and so forth. But the increasing diversity in Christian belief and practice from, say from the sixteenth century onwards, was also reflected in the flowering of new hymn writing, with reformers determined to replace much of what they considered to be popish superstition with pure biblical doctrinal hymns. As the churches became more identified as catholic or evangelical or liberal, so too do the hymns. Take the Victorian classic, ‘The Church’s One Foundation’, written by John Stone in 1866 with the deliberate aim of countering what was perceived as the heretical writings of Bishop Colenso of Natal. Such a hymn, line by line, emphasises the traditional orthodoxies of the Christian faith in a way which is both triumphalist and dogmatic. A century later in the 1960’s saw the emergence of new hymns for the twentieth century, often relating to issues facing contemporary society but rather unsatisfactorily represented in the standard hymn books hitherto. Writers such as Sydney Carter, Fred Kaan, John Bell and many others were part of the explosion of new hymnody which we are so used to today.

Words matter, they can build up or tear down and as St James reminds us in the third chapter of his letter, the tongue can be a blessing or a curse. In the second half of the twentieth century, many progressive Christians felt that too many hymns used militaristic language, albeit it metaphorical, in describing the Christian life. ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ seems perversely inappropriate in a century which had seen so many lives slaughtered in world and regional wars, sung in the name of a religion whose founder was called the ‘Prince of Peace’. Similarly as women were trying to shake off the shackles of a patriarchal possessiveness in so many countries across the globe, the masculine nature of the language of hymns seemed increasingly offensive. “Rise up O Men of God’, written in 1911, when most churches were led by men and attended by women, would probably not be chosen today by most clergy.

And so gradually hymns came to be changed, modified, dropped or forgotten and replaced by a richer and more comprehensive array of subjects and topics, contained in a wealth of new hymnbooks. Today however there remains a most challenging issue – how do hymns reflect a more radical understanding of God, Jesus and Christian theology in the light of two hundred years of biblical scholarship, of openness to the insights of other faith traditions and honesty to the ambiguities and complexities around the very nature and existence of “God”?

Let’s take, for example, the thorny doctrinal matter of substitutionary atonement and penal substitution in relation to the death of Christ. Stuart Townend’s hymn, “In Christ Alone’ remains very popular but do we really believe in the kind of God depicted in the hymn- ‘Till on that cross as Jesus died, the wrath of God was satisfied’? I guess that many people who enjoy singing this hymn – just watch them on Songs of Praise! – don’t really believe in a wrathful God who seems to get satisfaction from seeing ‘his’ Son die in agony on that cross. But the tune is good!!

So where do we go from here? I would argue that choosing hymns in worship is a heavy and yes, joyful, task and responsibility for any worship leader and must be undertaken carefully, intelligently, theologically and pastorally. Andy Thomas again:

Avoid lyrics that reinforce stereotypes and prejudice. It is not a loving way to minister to blind people in the congregation to consistently choose hymns that treat blindness as a metaphor for stubbornness, for instance. Similarly with patriarchal and other forms of exclusive language.

Hymn choices should be responsive to significant issues facing society, encouraging the community to reflect on (for example) modern forms of slavery, or how we treat the Earth and its resources. Seek out lyrics that are not overly preachy – as Brian Wren puts it, that “brings [one’s] understanding of the Bible into conversation with [one’s] knowledge, experience, and understanding of today’s world”.

Select distinctive hymns that celebrate the diversity in the worshipping community in all its forms, as well as hymns that are sufficiently non-distinctive to enable the diversity within the community to find themselves within the lyrics and music. Short and simple chants, such as those from the Taize and Iona communities, lend themselves to this.

(Andy’s article can be accessed below)

There are many resources to help those with the task of hymn choice. ‘Hymnquest’ is by far the most useful on-line tool and accompanying this article is a list of publishers whose titles and hymns add tremendous variety and theological sense to the corpus of hymns. If this short article can at least provoke a discussion about the hymns we sing, it will have achieved its aim. Consider these kind of issues and questions:

Which are my favourite hymns and why? Often our personal journey and our own background and experiences and personality might determine our preferences.

Which hymns do we not enjoy singing? Why? Are there words or phrases that upset or offend us? Are there negative associations for us?

Should there be a diverse economy of hymns in any worshipping community, to try to be as inclusive as possible or are there hymns which would never be sung and why?

Why not invite people to write their own hymns and discuss them?

Andy Thomas concludes:

Church music is about far more than just making a beautiful sound. It is about building the body of Christ by engaging and ministering to everyone, in all their diversity, as listeners and participants. It is about transforming individuals and communities to become more Christ-like in the way they act towards others. Church music is just one catalyst in this process, but an important one; one that can contribute significantly or, in some cases, reverse it altogether. It is key, therefore, that we think creatively, carefully and sensitively when approaching the selection and singing of hymns.

Author/copyright permissions

Reproduced with permission

Photo Credit: Michael Massen on Unsplash |